April 08, 2024

The Forgotten Stories of Black Women Weavers in America

Our ancestors are cardinal guides—vital mentors in uncovering the lessons of life. In the lands they once walked, we are the seeds they sowed and the legacies they bestowed. For some of us, those seeds are easily found; while for others, it takes a lifetime of yearning to uncover the magic of our origins. Lineage epitomizes the narratives of personal revival and cultural emancipation.

What does it mean to truly carry lineage? How do we honor the souls who came before us in the lives we lead? They’ve graciously left us with threads of connection, but to configure them into a tapestry– a prism of truth–appears to demand a cosmic resilience. To our pleasant surprise, this celestial virtue is intrinsic, gifted to us by ancestral figures—mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers, aunts and uncles—whose love and legacy resonate as a harmonious melody within our hearts.

Just like the gifts from our ancestors, art is the gift that connects us all. In the conquest for answers bigger than ourselves, art serves as a tool to translate the unimaginable, the unsaid, and the forgotten. For millions across the world, ancestry is a complex paradigm of stolen history, where art and creation ornate the unknown. Attuned to the weight of ancestry’s significance, we spoke with master weaver and VAWAA artist Karen, who is narrating the tales of her ancestors through fabric.

Karen at work in her studio in Alcalde, New Mexico, United States

The Healing Power of Weaving

Karen grew up in Los Angeles, California. The echoic freedom songs of the Civil Rights Movement were a score to her early childhood. Being one of 29 children involved in voluntary busing, her Black girlhood was a social experiment of tolerance and performance. For Karen, making sense of the world through the eyes of a child bearing the brunt of hatred was incredibly traumatic; but through cloth, she was able to find healing.

“My mother did not like bored children,” Karen told me. Made a textile master at an early age, Karen was taught the foundations of seamstressing by her grandmother and mother. By the age of 8, she had made her first dress and was able to sew her entire wardrobe by middle school.

Her grandmother, a Jamaican immigrant, was “the keeper,” she told me. Spending every day with her until her death when she was 17, Karen would revel in family mementos and photo boxes. Her curiosity for her history and life’s context was powerful to her even as a young child. Yet, she never realized the seeds of storytelling her grandmother was laying down for her own legacy.

Though her childhood was filled with the wonders of cloth, Karen abandoned this talent as a college-tracked high schooler until her final semester—where she discovered the wonders of weaving. “At that point, I was really trying to figure out what I was going to do with the rest of my life. I had decided to let myself take art classes.” Taught by a recent graduate, she took a class in an off-loom weaving project. With a daily 90-minute bus commute to school, Karen worked on that project. It was then that she had an epiphany: “I could do this for the rest of my life.”

For Karen, it was the place where magic could happen. Going on to take weaving courses at Laney College, and securing an apprenticeship with master weaver, Ida Grae, Karen embraced the presence required for off-loom weaving. “I would allow myself at least three months to do a tapestry off-loom. So, it was really not a place for speed; it was a place for being grounded into my space.”

Off the loom, Karen crafted a fabric of truth reflecting her own essence. However, as is often the case with art, scrutiny was inevitable. Soon, the very industry that had fostered her personal enlightenment attempted to ostracize her.

The Forgotten Black Women of American Weaving Traditions

The dawn of the Industrial Revolution was brought on by human genius. Technology and innovation optimized tradition for the modern world and industry was forever changed. In 1733, American inventor John Kay revolutionized the textile industry with the Flying Shuttle. Used with a traditional handloom, the flying shuttle was a crucial tool in textile efficiency. This invention soon became a pillar—and was a key development for the backbone of America’s textile industry: Enslaved women weavers.

Flying Shuttle, Invented by John Kay in 1733

Textile weaving was a crucial role for enslaved Black women in 18th century America. Responsible for the development and global success of American textile production, Black women are rarely credited with recognition for their contributions to this country’s early economic success. The matriarchs of American fabrics, Black women and their children, toiled in indigo and cotton fields, trained in the craft of weaving.

Under the tyranny of enslavement, Black women endured the threat of family destruction, sexual violence, and death. Through these conditions, Black women translated stories into their looms. Tales of history, family, and womanhood are deeply connected to the American tradition of weaving—for Black women, these stories built a nation, yet are reserved to the background to be forgotten and overwritten by racism and misogyny.

In Karen’s pursuit of weaving, she experienced the same disregard for her skills by white audiences. She wanted to tell stories; stories that were birthed out of her frustrations with the world. To put these emotions on the loom was healing, and her work was profoundly impressive. However, the rejection was too painful to continue; so much so, that Karen decided to pursue academia with a focus on art and anthropology.

A close-up of Karen's textile process

The Genealogy of Weaving

The coveted genius of Black women weavers is threaded through Karen’s work. Pursuing anthropology shifted the critical lens to herself as the maker—not the perceiver. That period was completely detached from the pressure to validate both herself and her creations. Karen says, “I figured if my family made me laugh, and made me cry, and made me go through so many different emotions, that there may be someone else who might find it interesting.” This mindset prompted her to begin showing her artwork again, ultimately pursuing a graduate degree at the University of California Davis.

Taken back to the days when the dominant white perspective of art and textiles felt exclusionary and dominating, Karen decided to enter the conversation from a cultural standpoint and answer the lifelong question: What is the history of Black American women weavers?

This question, coupled with the concept of ownership led her on a 2300-mile pilgrimage across the plantations of “The New South.'' Traveling mainly in the Lowcountry, the reminiscence of colonial America still hums in the soil. In our conversation, this recount shook me. Karen says, “The biggest surprise was that the land talked. I had visions when I was on plantations.”

At Boone Hall Plantation in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, Karen was surprised to encounter a historian on the grounds that acknowledged the existence of the enslaved. Though she ventured out to explore the grounds, she had no desire to go into “The Big House.” The preserved slave quarters, postured in rows with rings of dusted dirt paths guided Karen to the labor fields where ancestors worked, lived, and died. She then met a woman whose maiden name was Boone; her family was from South Carolina. Together, they walked out onto the viewing platforms overlooking the fields that spun the dreams of slaves into riches for America.

“We had the same experience. We had visions of people picking cotton. We talked about it as we walked back to rejoin the group. That was the first out-of-body experience on that trip,” she reflected.

Upon returning to California, Karen went to lunch with friends and entered a coin shop for souvenirs. Noticing the plethora of postcards, she was curious if the shop owner had any postcards with Brown people on them. “He said, ‘I do, but I don’t think you’re gonna like them.’ And I said, ‘Oh, please bring them out for me.’” What she was handed inspired one of her most coveted tapestries: Spirits Cry.

Printed on that postcard was an image of a Black child sitting atop a bale of cotton. Dating back to the early 1900s, that postcard–that image– serves as a poignant reminder of the enduring legacy of ancestral pain. The keen anguish we feel for those children. The echoes of souls yearning for salvation. The spirits that still cry.

SPIRITS CRY, 2000, handwoven, mixed media, indigo, linen, 36 x 52 in; employed the devoré technique (a process involving cellulose burning, commonly utilized in fashion) to etch the letters onto the tapestry

Women Weavers and Tapestries of Truth

Today, we know so much about the beauties of textiles, but through a Eurocentric lens. From colonial economics to contemporary techniques, there is an entire demographic of historical master weavers who go unrecognized. This reality inspired Karen to survey her own history because Black women weavers are essential to the history of weaving.

As the numbers of Black weavers across the country reach record highs, there is still a long way to go in diversifying the stories told through cloth. Karen is a testament to the significance of uncovering the hidden legacies of Black women weaving tapestries of truth in America. As the perception of the craft remains gate-kept by the horrors of misogyny and racism, weavers like Karen are using their art and platforms like VAWAA to share the rich history of weaving in Black and American tradition.

“Everyone chooses their own approach, but I fell in love with history very young. There were so many techniques that different cultures used to heal. I look for similarities, rather than differences. I just want to be able to put the marks on the paper—so people don’t have to go through what I went through.” Thinking about the consequences of modernization that causes culture to be lost, Karen’s goal is to leave the world a better place.

While there remains a significant journey ahead to dismantle the racist and misogynistic barriers within the weaving community, Karen remains hopeful. She admires remarkable textile artists such as Nneka Jones and Gary Tyler, who are leveraging their talents to spotlight cultural issues and honor the legacy of Black textile artists through their fabric creations.

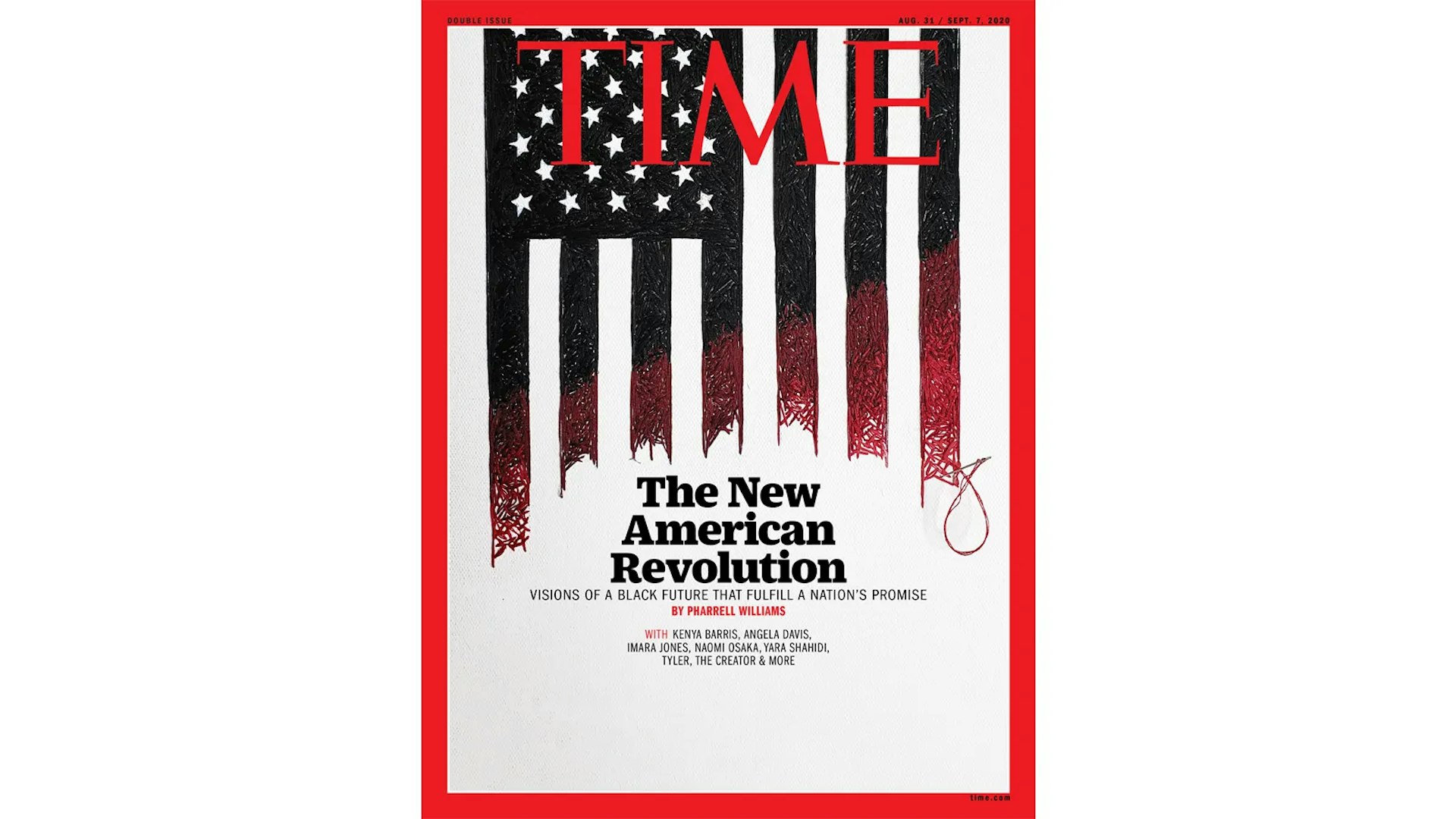

TIME Magazine, August 2020 issue; Nneka Jones crafted the artwork showcased on the cover by tracing the outline of the black stripes onto the canvas using stencils, then meticulously hand-embroidering them with black thread

“I don’t want anyone to come out like me; I want to engage with artists and meet them where they are.” As a master weaver with VAWAA, Karen is keen on who her guests are and where they want their art to go. Experienced or not, Karen wants to get to know you! With weaving, it's about connection. The aim is stimulation, not commerciality. Encouraging exploration and embracing the unexpected, she invites you to experiment with techniques.

Above all, she’s about emphasizing that your life's encounters serve as the threads binding your individual odyssey to your artistic expression. Introspection, integral to the art of weaving, unveils the magic within. The threads of heritage escort you towards redemption, akin to the guiding hands of your ancestors accompanying you every step of the journey.

Written by Tyler Pharr

Explore all mini-apprenticeships, and be sure to come say hey on Instagram. For more stories, tips, and new artist updates, subscribe here.